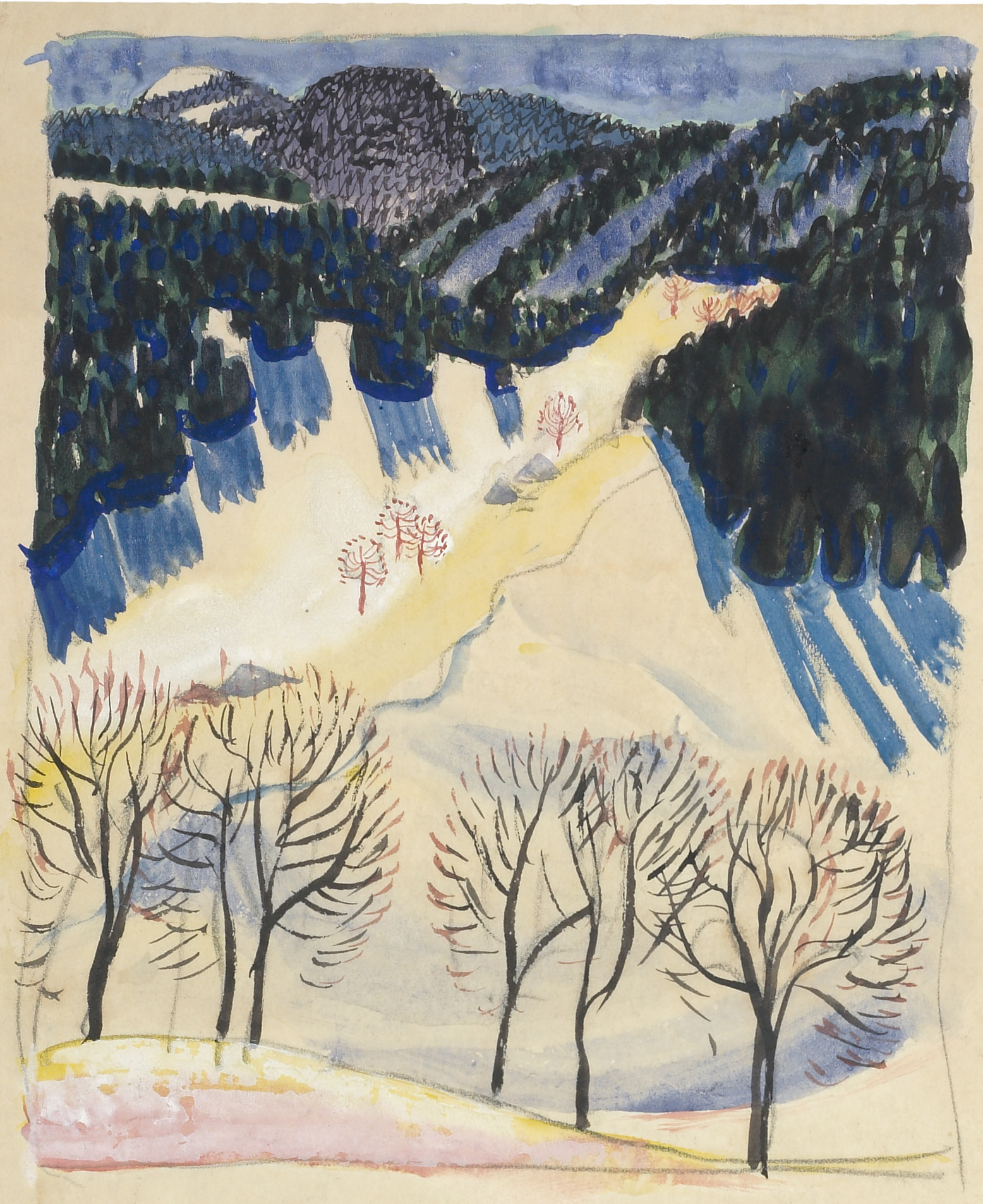

1907-1911: The voyages of initiation

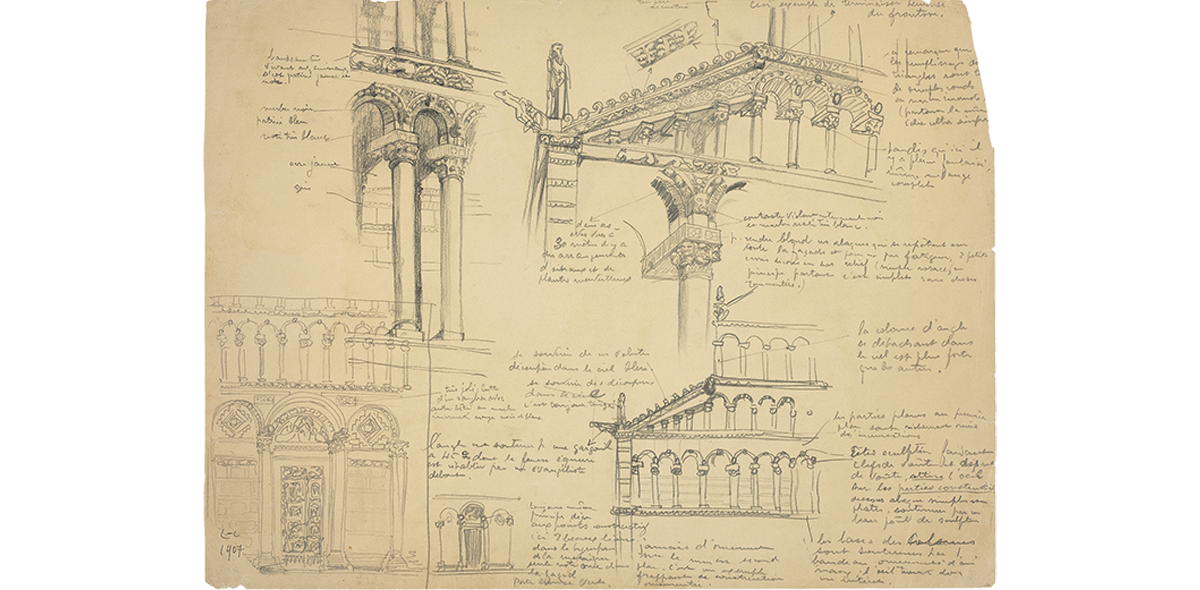

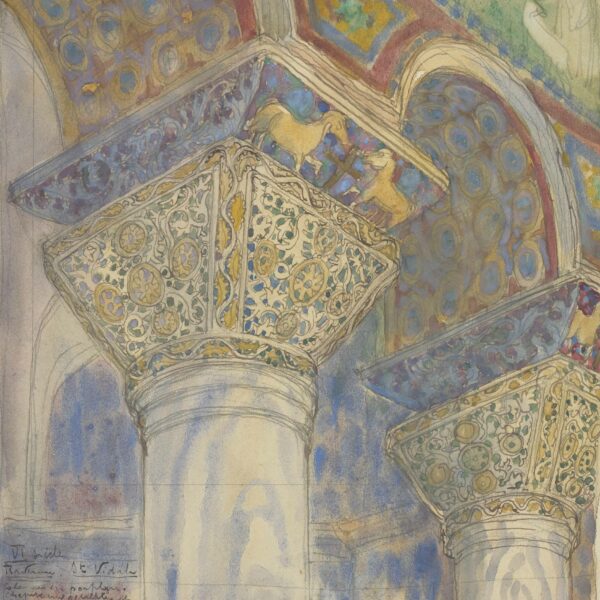

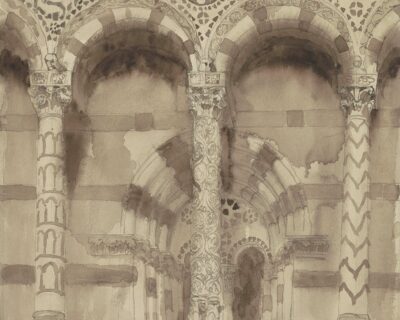

Between 1907 and 1911, Le Corbusier, still just Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, crisscrossed Europe to discover the arts, architecture and beauty of the world. A man with the soles of the wind, Le Corbusier learned his trade on zigzag journeys. During these years, he amassed an insane quantity of notes and drawings that would inspire his work for the rest of his life. These moments away from home created an extremely rich correspondence in which he depicted his journeys, his experiences and also his sensations.

1907

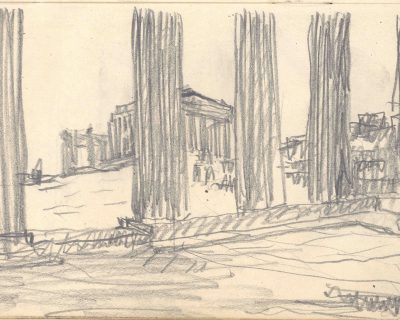

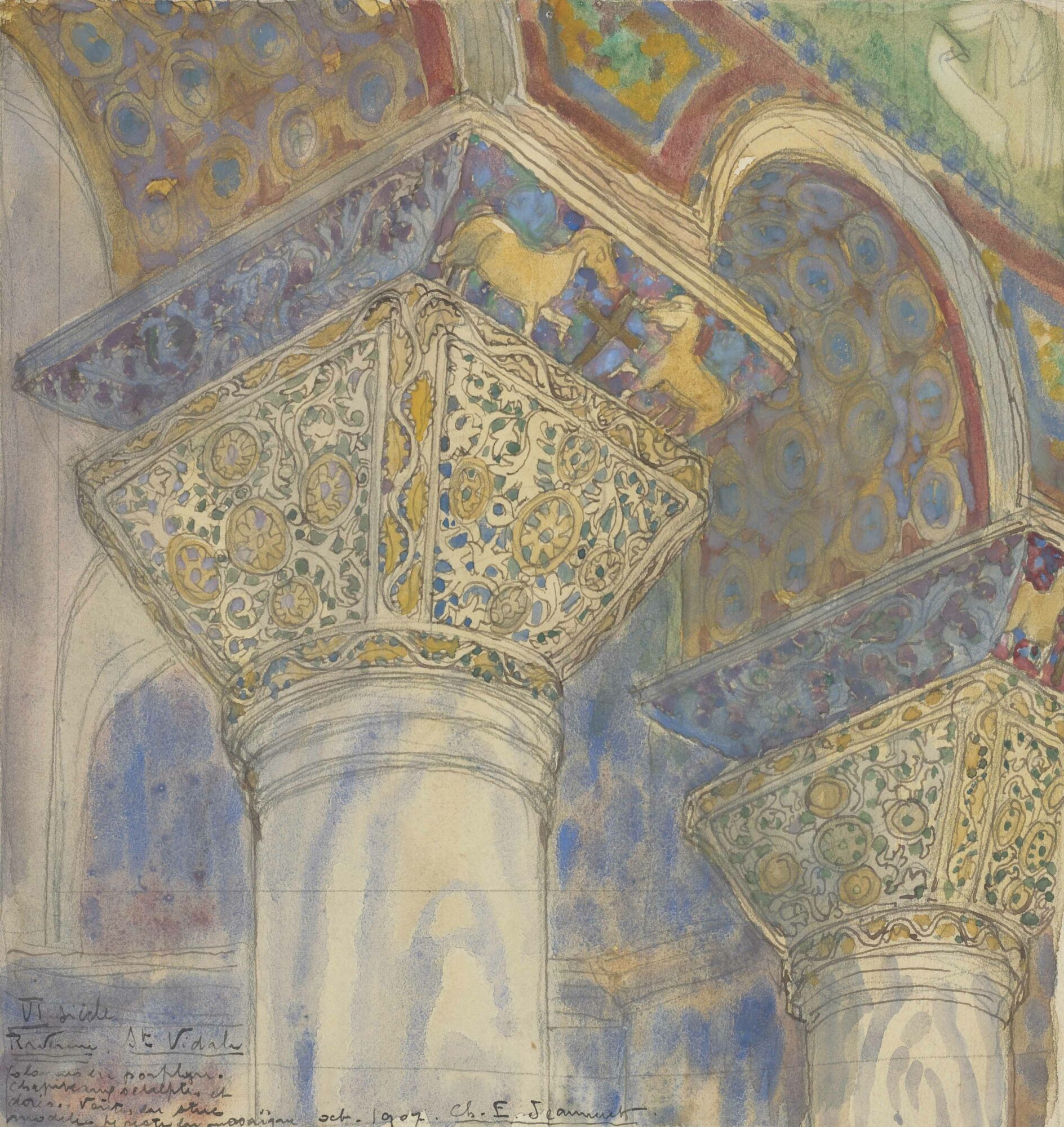

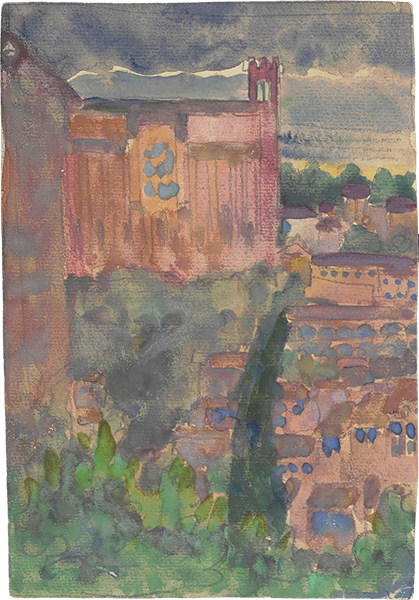

Thanks to the money earned from the construction of the Villa Fallet (1905-1907), Charles-Édouard, on the recommendation of his master Charles L’Eplattenier, became emancipated and left for Italy, where he crisscrossed from Tuscany to Veneto. Alongside his extensive correspondence, Charles-Édouard filled his notebook with drawings, in situ discoveries and the emotions he felt in front of the paintings in the Uffizi Museum, the Carthusian monastery of Ema or the setting sun in Ravenna. The architect’s Grand Tour gave him the opportunity to perfect his culture and training.

“It is as a colorist, and as an artist just as much, that I’ve enjoyed Italian landscapes so intensely; here, the foliage before falling turns gray, a superb fine gray; the meadows remain intense green, and the plowed fields alone give the vibrant note. The earth of Italy is extraordinary; it is salmon red, tile red, and with the few vines that here and there turn a bright lemon yellow, it forms what the famous fresco artists have rendered on their walls, a feast for the eyes and the imagination”. October 1907

Arriving in Vienna in November 1907, he continued his architectural and musical training, while working remotely on the Stotzer and Jaquemet.

1908-1909

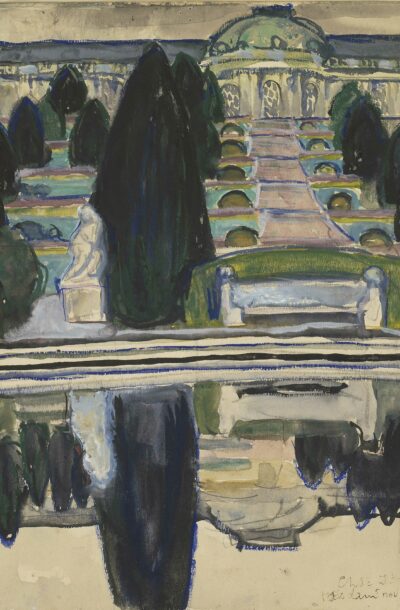

Memories of Germany and Austria left a bitter taste. Spurned by Viennese architects, Charles- Édouard over-invested in his move to Paris, which he saw as the only way to pursue his apprenticeship and establish himself professionally. Like many artists before him, he settled in the heart of Paris, at 9 rue des Écoles, in a room at the Hôtel de L’Orient. This dreamed-of Paris became a place of artistic innovation and industrial modernity.

Paris became the place of his education: “In Paris there is Notre Dame, and Versailles and everything, the Louvre, the Trocadero, it is crazy to want to say, it is the City of Light. In museums, I educate my soul and open my mind, laying solid foundations, principles. In an office, I learn the trade, and I will be studying on the side. All this will take a long, long time, with days and days lost. I will be full of disillusionment and resentment, but it will all be French and I will be able to volunteer and break down doors. Like a tourist, Charles-Édouard travels from the Sainte-Chapelle to the Musée Guimet. Le Corbusier felt drawn to the Parisian metropolis, which offered itself as a place of creative and social possibilities.

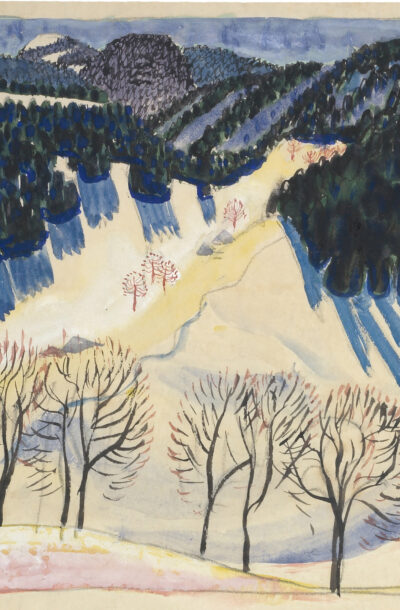

Autumn 1909: Return to La Chaux-de-Fonds. Le Corbusier builds the Stotzer and Jaquemet villas.

1910

In early December 1909, Charles-Édouard left Paris for La Chaux-de-Fonds to spend the festive season. Between January and March, he becomes involved in the creation of the Ateliers d’Art réunis association. Always keen to complete his training, and on the recommendation of his master Charles L’Eplattenier, he travels to Germany to carry out a study of decorative and industrial arts.

After short stays in Munich, Karlsruhe, Stuttgart and Ulm, he lived in Munich until October 1910. In addition to his studies, he was keen to receive architectural training. He sought out internships with the most renowned architects: Peter Behrens, Herman Muthesius, Bruno Paul and Theodor Fischer. The latter held him in high esteem, receiving him on several occasions, but without offering him a job. Confined to the role of tourist, Jeanneret once again set out to discover German cities, the embodiment of modernity. He spent seven days in Berlin, where he visited a number of major exhibitions: “Städtebau”, “Allegemeiner Städtebau”, “Ton-Talk Cement” and the “Sezession”.

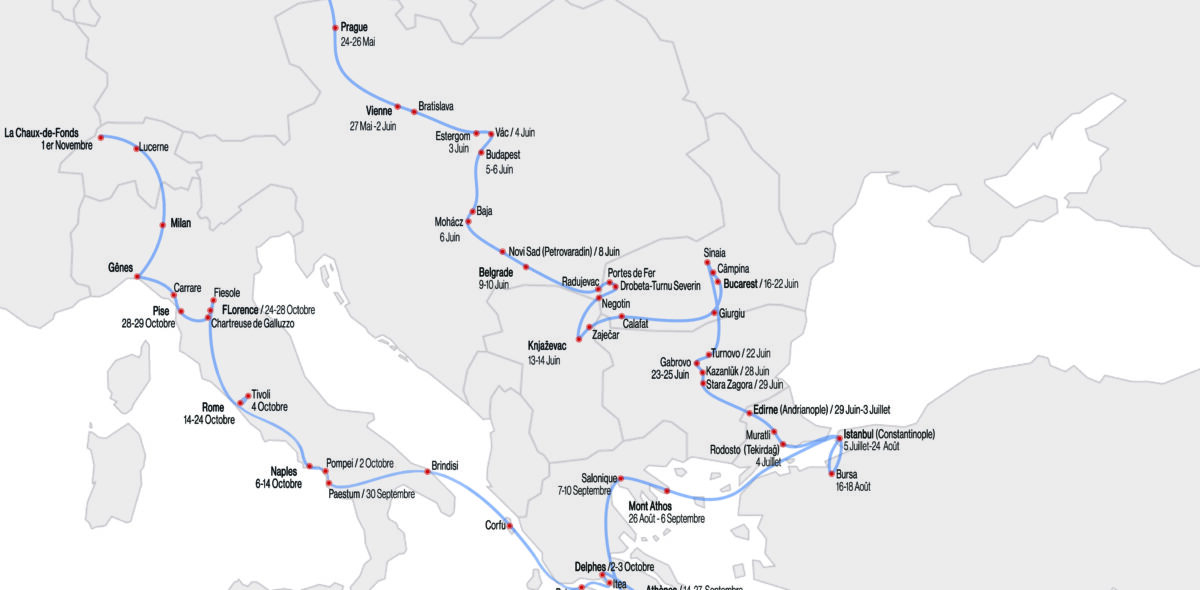

Back in Munich in June, he begins work on his manuscript for The Construction of Cities, based on a study of German town planning. While frequenting the literary salon, he met his future mentor William Ritter, with whom he struck up a close friendship. Ritter encouraged him to visit Prague and Budapest, and to travel to Turkey via Serbia and Romania. During the same period, he attended a Werkbund congress. A little later, he met Auguste Klipstein, an art history student and future companion of the “Voyage d’Orient”.

Jeanneret returns to La Chaux-de-Fonds to spend a summer with his family. Back in Munich in September, he again unsuccessfully applied for a job with Fischer. In October 1910, he reunited with his brother Albert in Hellerau, who was studying with the musician Emile Jaque-Dalcroze.

After much persistence, Peter Behrens finally hired him on November 1, 1910. Yet the young Jeanneret remained dissatisfied, complaining not only about working conditions but also about the content: “At Behrens, you do not do pure architecture. It is all about facades.

Constructive heresies are abundant”. On April 1, 1911, he left the studio with a mixed record.

Contrary to the wishes of his parents, who imagined a German career for him, Charles- Édouard had other aspirations. From Germany, he planned and conceived his trip to the Orient.

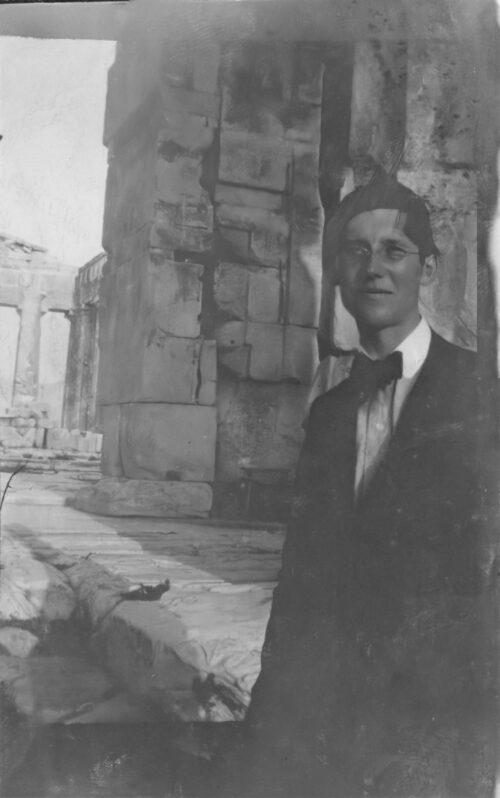

“So this great journey is a small one. For these eight months, which will complete my life as a young man, which will be the crown and coda of my studies, I am going to spend in Constantinople, Greece and Rome.”

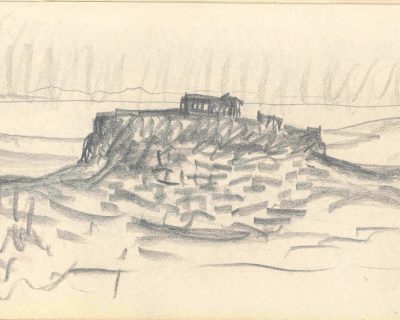

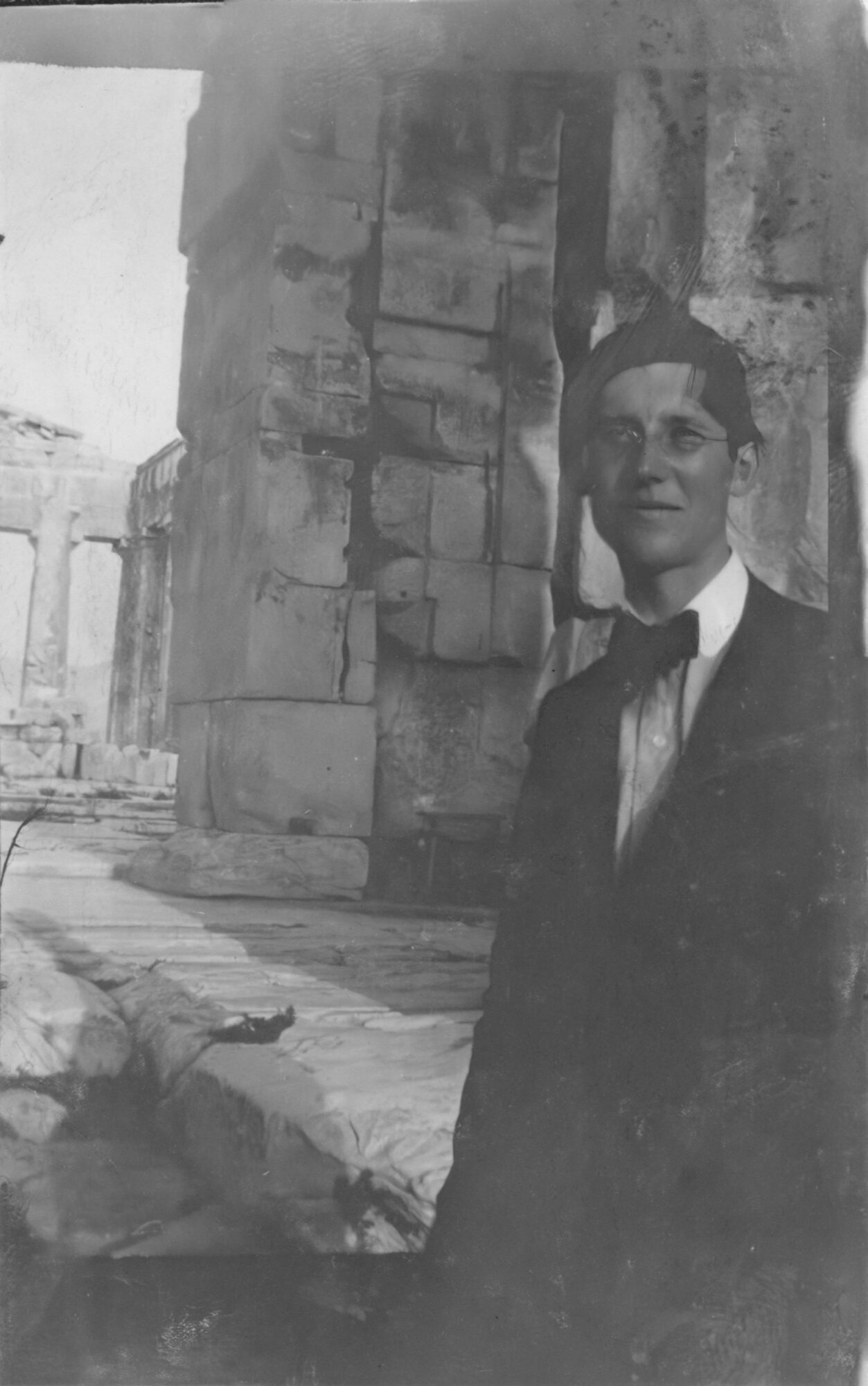

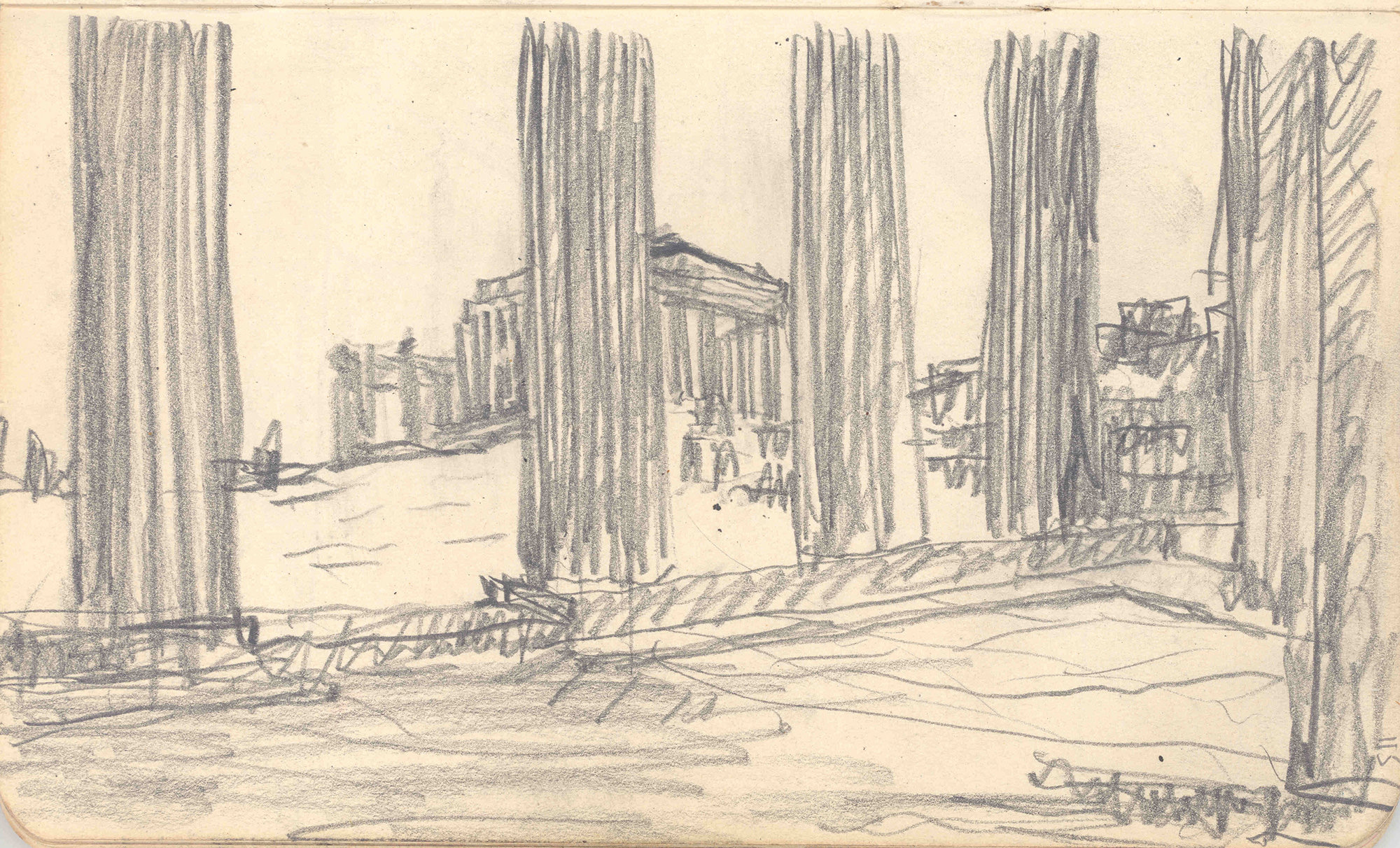

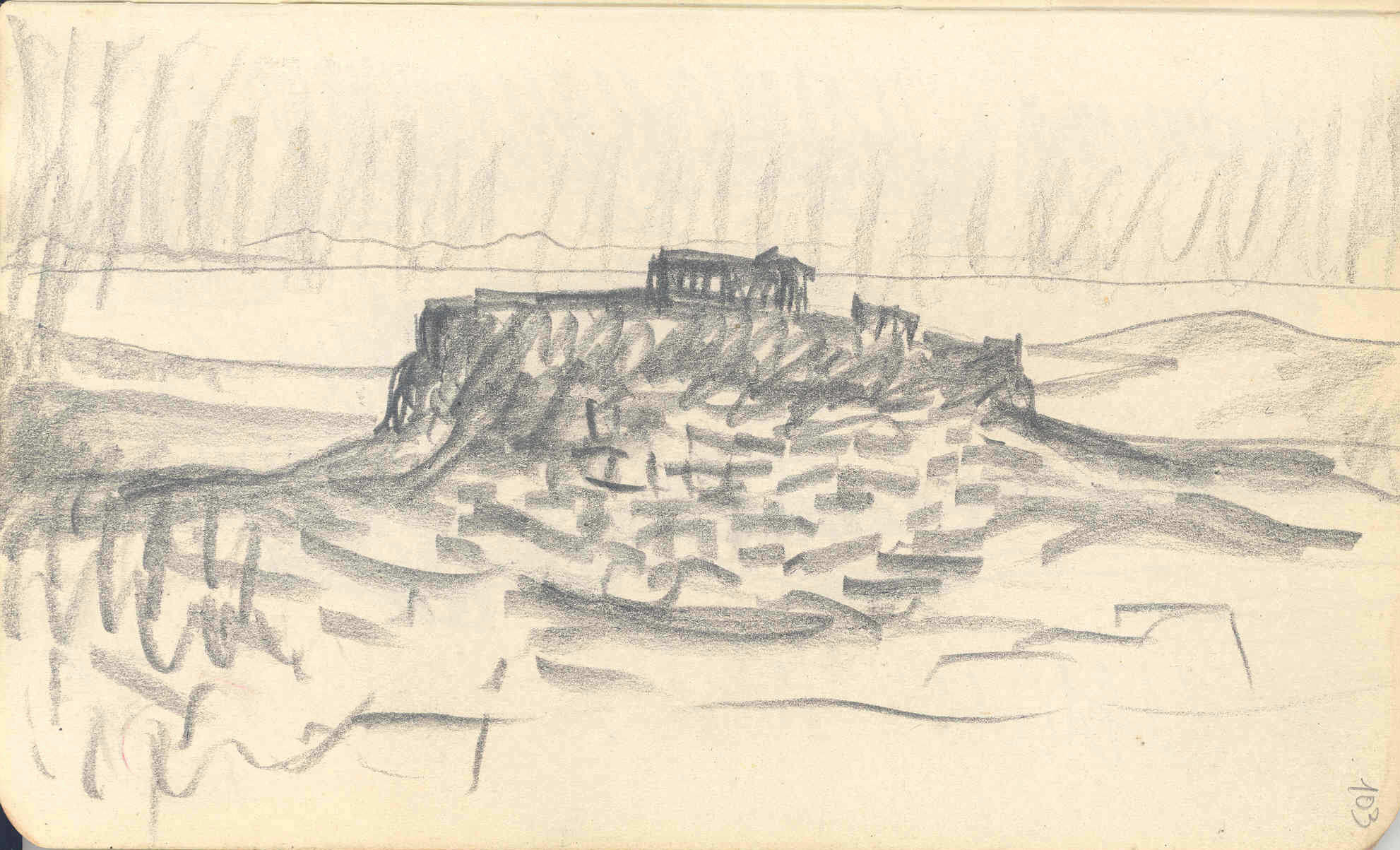

1911

It was in June, when he arrived in Prague, that this new initiatory opus began in earnest. As he criss-crossed the Balkans, he was already considering Greece and Turkey as his ultimate destinations. Most of the letters are written from “Constantinople”. He describes the city and its special features. The letters were also intended to keep him up to date on current events in La Chaux-de-Fonds, particularly those concerning the École d’Art and his future professional ambitions. His parents act as judicious information relays. In addition to the importance of immediate discovery, these correspondences shape and fix the expression of his impressions and emotions.

Immortalizing this itinerary in drawings and photographs, the young Jeanneret also captured his memory in articles published in the Feuille d’avis de la Chaux-de-Fonds. As he prophetically predicted, this great journey shed his youthful shell. Armed with his new intellectual baggage, he is a new man, about to return to Switzerland. Marie-Charlotte’s intuitive analysis was already causing her to dread her son’s return. In a letter dated October 22, 1911, she writes: “I’m afraid and delighted to see you again, afraid, because at last everything here will seem narrow and cramped; brains, country, atmosphere! And then, I pity you for coming back here; at the end of radiant countries, of fairy tales glimpsed and even lived, the Jura, the “clockers” inhabiting it, the simple, outdated customs, will seem painful to you and I expect that a spleen, of the enchanted Midi, of the fascinating Orient, will seize you and overwhelm you.”